Best Practices For Use Of Risk Registers In Bio/Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Operations

By Beth Fulton, Patrick Mains, and Kelly Waldron, ValSource Inc.

Since the original publication of ICH Q91 in 2005, pharmaceutical manufacturers have increasingly embraced a quality risk management (QRM) approach to tackle quality risks within their organizations. As these organizations mature in their understanding of risk, the portfolio of known risks about their operations increases. This growth in risk data can complicate risk communication, the portion of the ICH Q9 QRM life cycle focused on sharing information about risk between decision makers and others, e.g., among departments and sites within a company, between industry and the patient, and between industry and regulators.

Risk registers can be a valuable management tool, ensuring decision makers have key information needed to fulfill their responsibilities. Risk registers should be one part of a holistic QRM program, also including risk assessments, governing policies, and procedures, and risk-based approaches embedded into the quality system. According to PDA Technical Report 54,2 organizations should not rely solely on risk registers to compose their QRM programs. A risk register can alleviate communication difficulties by capturing the existence, nature, form, probability, severity, acceptability, control, treatment, detectability, and other aspects of risks to quality within a centralized, controlled location.

Risk Register Definition

ISO Guide 73:20093 defines a risk register as a “record of information about identified risks.” NISTIR 81704 defines a risk register as "a central record of current risks, and related information, for a given scope or organization…both accepted risks and risks that have a planned mitigation path.” U.S. FDA, EudraLex, PIC/S, ICH, and WHO have not defined risk register in their published literature.

The most useful definition of a risk register closely mirrors the NIST definition: a centralized index of risks impacting a given scope or organization that meets or exceeds a defined risk level. This index includes risks that currently impact the organization/scope, including risks that cannot be mitigated and risks that have planned or ongoing mitigation activities, all of which have been reviewed and approved and (at a minimum temporarily) accepted by senior management.

Bio/Pharmaceutical Regulations And Standards Referencing Risk Registers

Having a risk register is increasingly becoming a regulatory expectation. In 2010, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) in the United Kingdom created an FAQ for Risk Registers.5 Unfortunately, the FAQ is no longer available on the MHRA website. MHRA’s FAQs on risk management indicated an expectation that organizations maintain a risk register (or equivalent titled document) that lists and tracks all key risks as perceived by the organization and summarizes mitigation of those risks. Additionally, the MHRA FAQs suggested that the risk register provide clear linkages to risk assessments and that the organization maintain an index of all risk assessments that have been executed and authorized. The MHRA FAQ also stated that a management process should be established to review management of risks, with the recommendation that this be part of quality management review. This recommendation mirrors recommendations within the PIC/S Aide-Memoire on Assessment of QMS Implementation,6 which states, “A model for Management Review is provided in ICH Q10. A risk register or equivalent is useful to facilitate review by both the company and the inspector.” Similarly, while ISO 90017 does not mandate use of a risk register, risks and opportunities are required inputs for management review meetings.

Despite the lack of specific requirements for a risk register, it remains a great place to capture and communicate risks. ICH Q9 does not mention risk registers, but states that risk communication is an integral part of QRM implementation. A risk register is an excellent way to facilitate communication within an organization. A risk register can capture important risks from risk assessments in a concise manner best suited for governance-level discussions.

Defining The Scope Of A Risk Register

A risk register is best scoped to capture risks for alignment at the most elevated organizational level that is feasible within the existing management structure (e.g., global, site). With an appropriate escalation process, most companies will only need a global-level risk register.

It is paramount for the organization to procedurally define what risks are entered into the risk register. The risk register should reflect the risk tolerance of the organization, which is often phase-appropriate, and should be incorporated within the QMS. As defined in ISO 310008 and discussed in context by Vesper,9 risk tolerance is the acceptable level of variation relative to the achievement of a specific objective, and it is often best measured in the same units as those used to measure the related objective. That is, an organization’s risk tolerance is the maximum amount of risk they are willing to endure or willing to impose upon their patients. Minimally, for quality risks to be populated in the risk register, the scope should include high risks with the potential for patient impact but may vary for different organizations. For example, organizations with clinical-phase products may wish to include certain additional risks that may impact clinical equivalence (whether or not they impact patient safety), while those with commercial-phase products may wish to also include risks that could jeopardize product supply or otherwise lead to a product shortage.

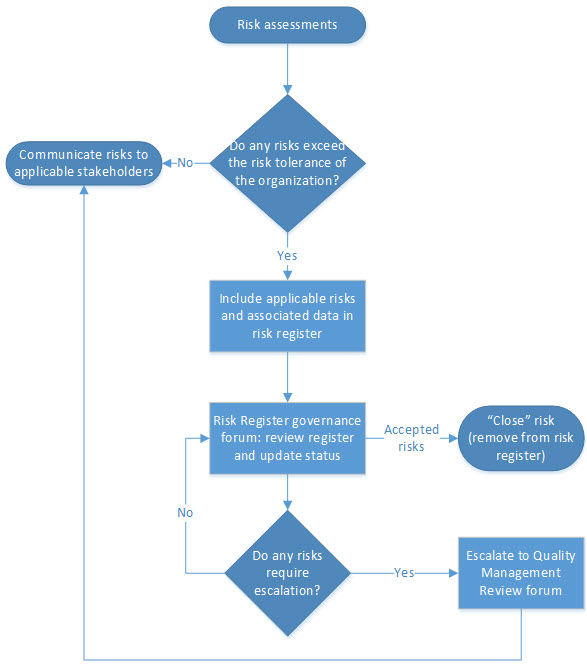

A clear escalation process should be established for ensuring risks that are in-scope are captured in the risk register in a timely manner. An example of this process is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Example risk register escalation process map

Structure Of A Risk Register

A risk register can be configured as a relational database or spreadsheet such that a dashboard and/or reports can be automatically generated for easy review. This dashboard/report should capture the total number of risks and the distribution of risks (i.e., how many high, medium, and low risks are present in the register).

Many firms manage risk registers through quality system software that facilitates relationships between risk assessments, such as corrective and preventive actions (CAPAs) and change controls (CCs). This capability to link parent risk assessments to child risks within the risk register and to link risks within the risk register to associated mitigation activities (CAPAs and CCs) can make quality system software preferable to document management systems for tracking revisions of the risk register. The best possible system would enable semi-automated or, optimally, fully automated updates of the risk register based on revisions to the associated risk assessments.

Management Review Of A Risk Register

The management review of the risk register should occur per established procedures within the organization. However, Quality leadership should reserve the right to increase the cadence of review if there is appropriate rationale. For example, if there are changes to senior leadership or risk owners, a management review should be scheduled to ensure that the new leadership is aligned with the previous decisions. If the new leadership is not aligned with the previous decisions, adjustments should be made to the planned mitigations. Some considerations for the review are as follows:

- Are mitigations on track to be complete per the approved plan? If not, what actions need to be taken to either achieve the desired timeline or accept a new timeline?

- Is the scope or intent of the mitigation still meaningful or relevant?

- Are there other options or improvements that will achieve the same outcome?

- Are there any unforeseen complications that have been identified during the execution of the changes to implement the mitigation plans?

- Did executed actions mitigate risk effectively as planned? If not, what needs to be done to improve the mitigation plans to meet expectations?

- Are there any changes to regulations or the organization’s risk tolerance that impact prior decisions or timelines?

- What observations have been made (internally or externally) that impact prior decisions or timelines?

Risk Register Linkages

Larger firms may benefit from having multiple risk registers ranging in scope from local (i.e., covering individual sites or products) to global (i.e., covering all sites and products). In these cases, a process should be established to enable the escalation of risks from the local risk register to a global risk register. This can help firms identify strategic risks and determine if any local risks apply to other sites or products. This process should also apply between local sites and global sites as well as with external stakeholders, such as partners, contract manufacturing organizations, key suppliers, and other external entities. External stakeholders should have their own means of escalating risks back to the contract owner, which should be defined in the associated quality agreement between the third party and the originating firm.

Risk Register Mistakes To Avoid

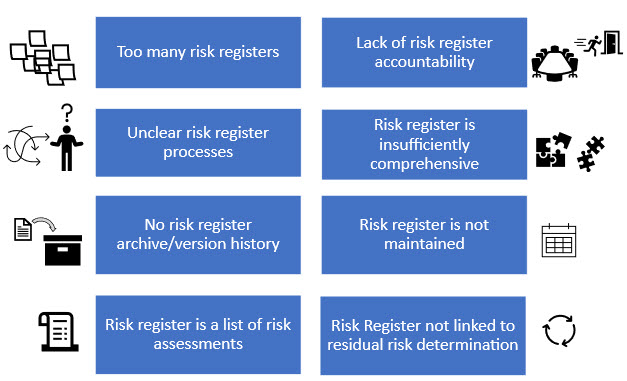

There are many easy mistakes to avoid in the creation and maintenance of a risk register. Some common risk register pitfalls are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Risk register errors

Having too many risk registers, e.g., a risk register for each department, is a common problem. This issue may cause duplication of the same risks across business entities with resultant varying levels of control throughout an organization. Additionally, the burden of maintaining those documents will increase with their number. Generally, a site level and a global level risk register are all that are necessary.

Lack of risk register ownership and accountability, i.e., accountability of individuals to actions within the risk register, is another pitfall to avoid. Actions must be assigned to individuals with an assigned and achievable due date (rationalized accordingly) and executed on the schedule prescribed within the risk register. Deviations to the schedule should be escalated to management as soon as possible so corrective measures can be taken. This is especially critical if the mitigation is associated with a regulatory commitment or could impact the patient.

Having unclear risk register processes (or entirely lacking a process for risk register management) can cause issues. Risk register(s) should be governed by a standard operating procedure that describes how management review of the risk register is performed and what the level of risk tolerance looks like for the organization. Ensuring that the risk register process (including report generation, if needed) is not overly complex is critical to ensuring clear communication of risk within and/or between organizations.

Risk registers that are insufficiently comprehensive also pose problems. Oftentimes the risk register serves as the primary communication mechanism to inform leadership and other stakeholders of risks identified by the larger organization. The risk register needs to include enough background information and context about the risk to enable decision makers to fulfill their responsibilities. A risk register that merely lists a hazard and a risk level may not be adequate in cases where stakeholders have no prior knowledge of the originating risk assessment. In these cases, the risk question, scope, likelihood, and severity for each risk on the register may also need to be included.

Failure to archive historical versions of the risk register is another area where many organizations make mistakes. Once a tracked risk has been mitigated so it is as low as practicable, it should be reviewed, accepted at the new level, and, if appropriate, archived from the risk register. Legacy or superseded versions of the risk register must be maintained with an appropriate revision history so that they may be presented and discussed during audits and inspections.

In support of the revision history, minutes should be maintained to track changes and decisions that were made due to management review, as they can be informative to the discussion that occurred at the time and will provide important context. This is important, as questions about the risk register and its history and changes are becoming a common topic during audits and inspections.

Failure to maintain the risk register in current state is another common defect; the risk register is meant to reflect an organization’s risk tolerance at the current moment in time.

An out-of-date risk register can indicate lack of management awareness of organizational risks and lack of a concerted strategy for weighing risk against benefit.

Confusing a risk register for a list of risk assessments is another frequent misconception. While the archived MHRA FAQ5 specified that a list of risk assessments should exist (with clear linkage to the risk register), some parties have equated that list to the risk register itself. It should be noted that such a list can be automatically generated by query within most electronic document management systems.

Failure to use the risk register to spur residual risk determination is another possible flaw. The risk register should be used to prompt (and track) residual risk determination within referenced risk assessments upon demonstration of effectiveness of mitigations. Use of the risk register to drive residual risk determination ensures timely assessment of residual risk both within the original risk assessment (where the escalated risk originated) and within the risk register itself where that escalated risk is tracked for management review.

Future State For Risk Registers

Eventually, we foresee that manufacturers will customize their quality systems software to include capability for risks to be carried automatically from risk assessments directly into the risk register. This functionality is desirable for several reasons:

- It will decrease repetitive labor (transcription) for quality systems personnel, allowing them to focus their energy on more value-added tasks.

- It will reduce the likelihood of certain compliance risks (e.g., mismatch between information within a risk assessment and the risk register due to a transcription error or due to revision of one location and not the other).

- It should reduce the time between a change to a risk assessment and subsequent update of the risk register.

As quality management software platforms mature, this automated capability will almost certainly become standard. Further maturation of quality management systems software also will likely include increased automation enabling scripted generation of reports and dashboards for report-out of risk register key performance indicators (KPIs). This should enable more efficient preparation and facilitation of management review. In addition, as machine learning is integrated into quality systems, it may even be able to proactively identify emerging trends or new KPIs within the risk register for discussion and analysis during management review.

The future state of risk registers is bright. Increased automation and implementation of machine learning in the generation of the risk register and synthesizing the outputs promises to improve performance of the manufacturing organizations that choose to pursue those advancements.

Conclusion

This article highlighted some best practices for the use of risk registers in pharmaceutical manufacturing. With the definition of risk register elucidated and an understanding of what regulations and standards require from a risk register, organizations can clearly define scope, management review actions, quality system linkages, and internal requirements for maintenance of risk register(s). Taking these actions will allow organizations to avoid common pitfalls associated with the use of risk registers for risk communication and more consistently supply high-quality products to patients.

References:

- ICH Q9 (R1). "Quality Risk Management" 2023.

- TR 54, “Implementation of Quality Risk Management For Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology Manufacturing Operations”, 2012

- ISO Guide 73. “Risk Management — Vocabulary.” 2009.

- Barrett, M. et al. "Nistir 8170: Approaches for Federal Agencies to Use the Cybersecurity Framework." NIST Computer Security Resource Center. (2020): 1-33.

- MHRA. "MHRA FAQs on Risk Management." 2010. https://www.ipqpubs.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/MHRA-FAQs-on-Risk-Management.pdf.

- PIC/S, PI 038-1. “Aide-Memoire on Assessment of QMS Implementation.” 2012.

- ISO 9001. “Quality Management Systems — Requirements.” 2015.

- ISO 31000. “Risk Management.” 2018.

- Vesper, J. “What Are Risk Appetite & Risk Tolerance In Pharma & Medical Devices?” Outsourced Pharma. 2022. https://www.outsourcedpharma.com/doc/what-are-risk-appetite-risk-tolerance-in-pharma-medical-devices-0001#:~:text=Risk%20appetite%3A%20The%20types%20and,to%20measure%20the%20related

%20objective.

About The Authors:

Beth Fulton is a consultant with ValSource. She has expertise in the development and implementation of innovative approaches to quality risk management (QRM), especially situational application of QRM tools and quality systems design and implementation for pharmaceutical, biopharmaceutical, cell therapy, and combination products. She has a BS in food science from Cornell University, an MS in zoology from University of New Hampshire, and an MS in food science and human nutrition from the University of Maine. She can be reached at bfulton@valsource.com.

Beth Fulton is a consultant with ValSource. She has expertise in the development and implementation of innovative approaches to quality risk management (QRM), especially situational application of QRM tools and quality systems design and implementation for pharmaceutical, biopharmaceutical, cell therapy, and combination products. She has a BS in food science from Cornell University, an MS in zoology from University of New Hampshire, and an MS in food science and human nutrition from the University of Maine. She can be reached at bfulton@valsource.com.

Patrick Mains is a senior consultant at ValSource. He supports organizations in the pharmaceutical, biopharmaceutical, and cell and gene therapy industries applying his expertise in quality risk management to all product types throughout their life cycles. Mains holds a BS in biochemistry and cell biology from the University of California, San Diego. He is a Project Management Institute (PMI)-certified Project Management Professional (PMP). With more than 30 years of experience in the biopharma industry, he has had various roles in quality control, project management, site compliance/inspection management, quality systems, and global quality across multiple organizations. Mains can be reached at pmains@valsource.com.

Patrick Mains is a senior consultant at ValSource. He supports organizations in the pharmaceutical, biopharmaceutical, and cell and gene therapy industries applying his expertise in quality risk management to all product types throughout their life cycles. Mains holds a BS in biochemistry and cell biology from the University of California, San Diego. He is a Project Management Institute (PMI)-certified Project Management Professional (PMP). With more than 30 years of experience in the biopharma industry, he has had various roles in quality control, project management, site compliance/inspection management, quality systems, and global quality across multiple organizations. Mains can be reached at pmains@valsource.com.

Kelly Waldron, Ph.D., manages the Quality and Manufacturing Science business units within the consulting division at ValSource, where she also serves as a senior consultant, and is a member of the Pharmaceutical Regulatory Science Team (PRST) at the Technological University Dublin (formerly Dublin Institute of Technology) in Dublin, Ireland. Waldron has particular expertise in the development and implementation of innovative approaches to quality risk management (QRM). Her expertise extends to various quality functions in the pharmaceutical, biopharmaceutical, and medical device industries, including quality system design, quality strategy and planning, deviations/investigations, CAPA, change management, data integrity, audit and inspection programs and response, and design control. She holds a BA in biology from Boston University, an MBA in pharmaceutical management from Fairleigh Dickinson University, and a Ph.D. in pharmaceutical regulatory science (thesis in QRM) from the Dublin Institute of Technology. She can be reached at kwaldron@valsource.com.

Kelly Waldron, Ph.D., manages the Quality and Manufacturing Science business units within the consulting division at ValSource, where she also serves as a senior consultant, and is a member of the Pharmaceutical Regulatory Science Team (PRST) at the Technological University Dublin (formerly Dublin Institute of Technology) in Dublin, Ireland. Waldron has particular expertise in the development and implementation of innovative approaches to quality risk management (QRM). Her expertise extends to various quality functions in the pharmaceutical, biopharmaceutical, and medical device industries, including quality system design, quality strategy and planning, deviations/investigations, CAPA, change management, data integrity, audit and inspection programs and response, and design control. She holds a BA in biology from Boston University, an MBA in pharmaceutical management from Fairleigh Dickinson University, and a Ph.D. in pharmaceutical regulatory science (thesis in QRM) from the Dublin Institute of Technology. She can be reached at kwaldron@valsource.com.