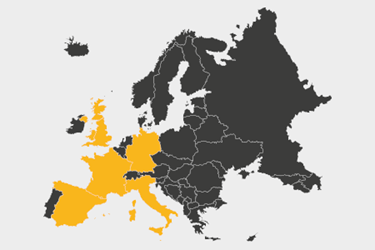

Biosimilar Automatic Substitution In The EU5: Current State & Future Outlook

By Marta Delgado, Ph.D., Decision Resources Group (DRG)

In spite of the initial high expectations for biosimilars to alleviate the healthcare economic burden and the many policies and initiatives put in place to encourage their use, initial uptake of biosimilars has been slower than anticipated, meaning their associated price reductions have not been quick to materialize. At present, automatic substitution of biosimilars at a pharmacy level is not practiced in the EU5. Recent and future changes in the EU5 market access environment and regulatory landscape may favor automatic substitution, but whether it is implemented and becomes an effective measure to sustain the biosimilar market is yet to be determined.

The Role Of The EMA In Automatic Pharmacy-Level Substitution Of Biosimilars

For more than a decade, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has been providing guidance on biosimilar development. To date, the European Commission (EC) has approved over 50 biosimilar products across 15 different biological classes, of which 16 were accepted in 2018.1 Although the EMA is responsible for evaluating biosimilar candidates for market approval, it does not provide guidance on the automatic substitution of a reference product with a biosimilar. Instead, each individual European Economic Area (EEA) member state has the autonomy to decide whether a pharmacist’s automatic substitution of a biosimilar is appropriate without the authorization of the prescribing physician or the patient. Except for some countries like Poland, where absence of specific guidance or laws has allowed automatic substitution to ensue, most of the EEA member states either prohibit pharmacy-level automatic substitution or allow for limited substitution only.2

Automatic Pharmacy-Level Substitution Of Biosimilars In France

France is the only EU5 market where a legal framework is in place for restricted automatic substitution of biosimilars. The 2014 Social Security Financing Law permits the substitution in treatment-naive patients of an originator and its biosimilar if they fall under the same ''similar biologic group,'' i.e., if the biosimilar belongs to the same group as the prescribed product, and if the prescribing physician has not explicitly prohibited substitution. To date, the National Agency for Medicines and Health Products Safety (ANSM) has created 14 similar biologic groups, listing 51 biosimilars in total, albeit the enactment of the law is pending for five years in the absence of an implementing decree with the details of the practice.3

While the introduction of pharmacy-level substitution has stalled in France, the uptake of biosimilars continues to be under great scrutiny. The French National Health Insurance Fund’s proposed cost-containment measures – which will likely be included in the Social Security Finance bill for 2020 – seeks to reduce public spending and increase biosimilar use by lowering expenditure on several prescribed drug classes and increasing financial incentives, e.g., through gainsharing agreements between hospitals and providers. Moreover, the French government aims to raise biosimilar awareness and comfort among healthcare practitioners and patients by publishing educational brochures on bioequivalence and interchangeability. This may prove to be a better strategy for biosimilar uptake than automatic substitution, given that physicians’ reticence to switch to biosimilars continues to be one of the main barriers to biosimilar use in the country, despite the increase in familiarity and comfort with biosimilars over the past years.2

Automatic Pharmacy-Level Substitution Of Biosimilars In Germany

German physicians’ acceptance of and prescribing experience with biosimilars, on the other hand, is high compared with the rest of the EU5 countries, mainly driven by the regional prescribing quotas in place for biosimilars of etanercept, erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs), infliximab, rituximab, and trastuzumab. Despite prescribing quotas being an effective measure to drive biosimilar uptake, office-based physicians do not always meet these quotas, even though they can be financially penalized for it. To resolve this problem and facilitate biosimilar uptake, DRG-interviewed payers in Germany have mentioned the necessity to force substitution of biosimilars at a pharmacy level, which could also equalize the substantial differences in biosimilar prescription quotas between regions.2

To date, the National Association of the Federation of Health Insurance Funds in Germany allows for limited substitution of biosimilars referred to as ''bioidenticals,'' i.e., biosimilars made by the same manufacturer on the same production line. In November 2018, the German Health Ministry presented the ''law for more safety in the supply of pharmaceuticals'' (known as GSAV), encouraging the use of biosimilars by proposing the automatic substitution of not only bioidenticals, but specific biosimilars on a case-by-case assessment. The Federal Joint Committee (G-BA) is responsible for setting up this new legal framework, which was expected to be executed in the first half of 2019. Negotiations are still ongoing between the G-BA and the German Health Ministry; however, two sets of recommendations or guidance are likely to become available: one for physicians, detailing how to conduct switching, and a second one for pharmacists, listing the biosimilars eligible for automatic substitution. This change is expected to happen by 2022, allowing for a three-year transition period to ensure physicians and patients are comfortable with its introduction.4

Though there is still significant uncertainty over the specifics of the GSAV, it is likely that, if approved, Germany will become the first EU5 country to implement automatic substitution of biosimilars at the pharmacist level.

Automatic Pharmacy-Level Substitution Of Biosimilars In Italy And Spain

On the other end of the spectrum are Italy and Spain, where it seems unlikely that automatic pharmacy-level substitution of biosimilars will be permitted any time soon. First, there is no legal framework in place for substitution at the level of the pharmacist in either market. In Italy, the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) released a second position paper in April 2018, providing biosimilar guidance and recommending their use in treatment-naive and established patients in cases where switching from the originator brand to the biosimilar can be justified for economic reasons. However, automatic pharmacy-level substitution of biosimilars is prohibited, and the position statement was not well accepted by the industry and healthcare practitioners who are against switching patients already undergoing treatment with a reference biologic. In Spain, biosimilars are not subject to the same substitution rules as small molecule generics and the current legislation details that automatic substitution of a biological product for another is forbidden without authorization of the prescribing physician and patient acceptance. Second, based on the opinion of DRG-interviewed payers, physicians’ preference for the originator product and opposition to switching continues to slow biosimilar adoption in both countries, due to concerns around the efficacy and immunogenicity of biosimilars. Moreover, interviewed payers in these markets mention that there is no strong reason to favor the use of biosimilars over the reference brand when the originator manufacturer reduces the drug purchase costs to match the price discount of the biosimilar developer. As stated by an interviewed Spanish DGFPS advisor, “Switching is not encouraged in Spain because there is not too much difference between the cost of the original and the biosimilar. If patients have been receiving the original, they will continue with that one. Also in Spain, they need the approval and the consent of the patient if the clinician wants to switch the medication of a patient.”2

Automatic Pharmacy-Level Substitution Of Biosimilars In he U.K.

In the U.K., pharmacists are prohibited from substituting a reference product for a biosimilar; however, the NHS encourages physicians to substitute biosimilars in its guidance, provided that the patient agrees with the treatment option. Switching patients from Remicade to the infliximab biosimilars Inflectra and Remsima has become a common practice in the U.K. and, with the launch of adalimumab biosimilars in October 2018, the biosimilars guidance now recommend that nine out of 10 treatment-naive patients and eight out of 10 established patients on the reference product should receive the best-value adalimumab within three and 12 months of a biosimilar entry, respectively.5

According to payers interviewed by DRG, most U.K. physicians agree with initiating patients on a biosimilar; however, they also mention that current measures, such as gainsharing between the NHS payers and providers – in which savings through cost-effective prescribing are split between the CCG and the hospital – are already effective in driving biosimilar uptake. For this reason, payers anticipate it will be unnecessary to grant pharmacists the authority to change the prescribed originator for a biosimilar via automatic substitution and believe any treatment switching should continue to fall under the prescribing physician’s responsibility. In the words of an interviewed NICE advisor: “I don't think we need to change the pharmacy-level automatic substitution policy. The U.K. has a lot of incentives already to encourage the use of biosimilars instead of the brand, so they're using more [financial] incentives than automatic substitution.”2

Future Outlook Of Automatic Pharmacy-Level Substitution Of Biosimilars In The EU5

In light of the recent changes in the regulatory landscape for biosimilars in the EU5, it appears (in the near term, at least) that only Germany will implement an automatic substitution policy. Though the exact details of how this will work in practice remain under discussion, automatic substitution at a pharmacy level will likely help to increase adoption of biosimilars and further improve cost savings in this market. Nevertheless, automatic pharmacy-level substitution of biosimilars will not impact biosimilars used in the inpatient setting, but only those prescribed in hospitals and dispensed by community pharmacies. Thus, a different approach focused on changing physicians’ behavior toward biosimilars may result in a better strategy to increase biosimilar market share in markets such as Italy and Spain, where physicians’ attitudes toward biosimilars continue to be a main barrier to biosimilar adoption.

As for France and the U.K., governments in these markets seem to have prioritized strategies other than automatic pharmacy-level substitution, such as financial rewards to hospitals and physicians, to increase biosimilar uptake. Yet there may be an opportunity to introduce or implement substitution policies in these markets if automatic substitution proves to effectively reduce healthcare spending in Germany.

Even so, it is still too early to predict what the overall outcome of automatic pharmacy-level substitution will be and how will this roll out in each EU market; whether it will significantly boost the biosimilar market in Europe or just become another measure with limited scope to drive biosimilar uptake, remains to be seen.

References:

- European Medicines Agency: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines (last accessed on 17th September 2019)

- Decision Resources Group, Biosimilar Insights, 2019

- ANSM: https://www.ansm.sante.fr/ (last accessed August 2019)

- German Health Ministry: https://www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/fileadmin/Dateien/3_Downloads/Gesetze_und_Verordnungen/GuV/G/GSAV_Bundestag.pdf

- NHS England: https://www.sps.nhs.uk/home/medicines/

About The Author:

Marta Delgado, Ph.D., is a business insights analyst in the Biosimilars Research team at Decision Resources Group (DRG), responsible for the analysis of the biosimilars market across four main therapeutic areas — oncology, endocrinology, immunology and nephrology. She provides her research on the market assessment of biosimilars on DRG’s Insights Platform. Delgado holds a Ph.D. in molecular neuroscience from University College of London (UCL) and a B.Sc. in biomedicine from University Pompeu Fabra (UPF), Barcelona. Prior to joining DRG, she worked as a research analyst at SKIM, specialising in advanced quantitative studies assessing the potential market opportunities to support life sciences companies in their business decision making.

Marta Delgado, Ph.D., is a business insights analyst in the Biosimilars Research team at Decision Resources Group (DRG), responsible for the analysis of the biosimilars market across four main therapeutic areas — oncology, endocrinology, immunology and nephrology. She provides her research on the market assessment of biosimilars on DRG’s Insights Platform. Delgado holds a Ph.D. in molecular neuroscience from University College of London (UCL) and a B.Sc. in biomedicine from University Pompeu Fabra (UPF), Barcelona. Prior to joining DRG, she worked as a research analyst at SKIM, specialising in advanced quantitative studies assessing the potential market opportunities to support life sciences companies in their business decision making.