CMS' Decision On Coding For Biosimilars: A Deeper Look

By Amy Duval, senior director of biosimilars, Decision Resources Group (DRG)

The November 2017 decision by CMS to change the coding practice for biosimilars in the United States is likely to have far-reaching consequences for these drugs, but will all downstream effects be positive? As the decision is applauded by various prescriber, patient, and industry groups, it is key to investigate the events that could ensue from the decision, and whether it will stimulate the U.S. biosimilar industry, which languishes behind that of other geographies.

The CMS Decision On Biosimilar HCPCS Codes

CMS’ decision to change the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) coding practice for biosimilars was lobbied by several biosimilar organizations, including the Biologics Prescribers Collaborative, the Alliance for Patient Access, and medical associations such as the American College of Rheumatology and the American Gastroenterology Association. This change will see biosimilars be given their own HCPCS codes from 2018 onward, rather than all biosimilars of one molecule being grouped under one such code, as was the case previously. Currently, only two biosimilars are subject to grouping under one HCPCS code: Pfizer’s Inflectra and Merck & Co.’s Renflexis, both of which launched in 2017 as biosimilars of Johnson & Johnson’s Remicade. HCPCS code modifiers were introduced by CMS for Inflectra and Renflexis to enable differentiation between the two — ZB for Inflectra and ZC for Renflexis. While this facilitated differentiation between the two drugs for monitoring purposes, it did not affect their root HCPCS code.1 Despite this adaptation, various prescriber, patient, and industry groups advocated for a change in coding practice for biosimilars, which CMS has announced it will now implement.

Why The Existing HCPCS Coding Structure Is Inappropriate

Under Medicare Part B, physicians are reimbursed for biologics according to the average sales price (ASP) associated with a particular HCPCS code plus 6 percent. Grouping biosimilars together under one HCPCS code could therefore encourage a downward spiral of pricing competition between biosimilar competitors; the cheapest biosimilar available under a grouped ASP would offer physicians a revenue-generating opportunity because prescribers would be reimbursed more than the drug cost (because it is priced below the ASP), as well as the additional 6 percent fee. This approach would also discourage use of biosimilars priced above the ASP. This pricing competition could result in a lack of reliability in supply because manufacturers may exit the market if they are unable to compete at such low costs, or it may even discourage manufacturers from entering the market at all as the opportunity for return on investment in developing a biosimilar is diminished.

Get a foundation in biosimilar products development, manufacturing and regulations in Barry Rosenblatt's course:

Biosimilars: Preparing For Opportunities And Challenges

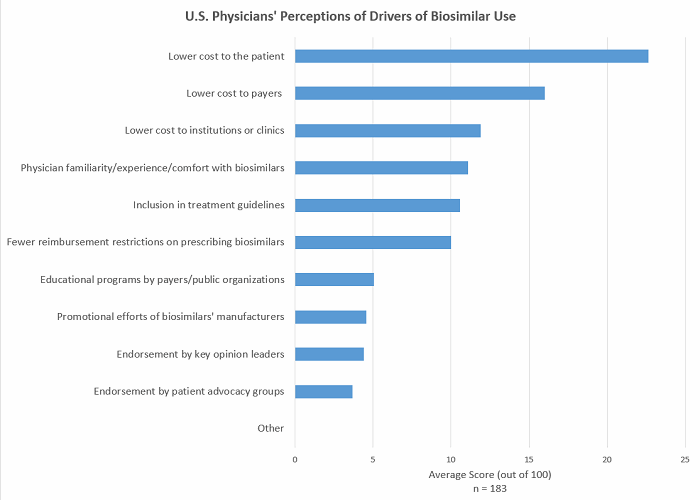

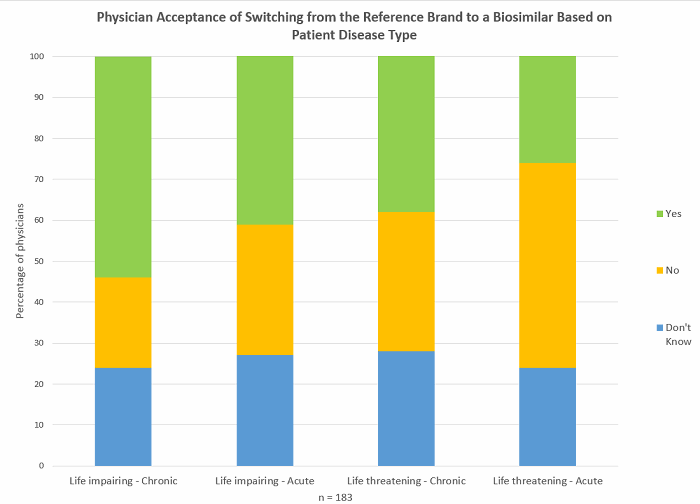

Designating individual HCPCS codes to each biosimilar will reduce the potential of less favourable reimbursement for certain biosimilars, allowing prescribing physicians more choice as to which biosimilar patients receive. Physician preferences for specific biosimilars may depend on several factors beyond cost, such as their inclusion in treatment guidelines, the data they have available, and marketing efforts (see Figure 1). Advocates for the coding policy change also put forward the argument that grouping several biosimilars under one HCPCS code could lead to inadvertent switching between biosimilars. At a time when physicians are yet to become fully comfortable with switching from a brand to a biosimilar (see Figure 2) and are demanding more data on the topic, switching between different biosimilars to the same reference brand, which is yet to be evaluated in clinical trials, is highly undesirable.

Figure 1 (Source: Decision Resources Group, survey data collected May 2017)

Figure 2 (Source: Decision Resources Group, survey data collected May 2017)

Industry groups have also raised concerns in the past that grouping all biosimilars under one HCPCS code could impact post-marketing safety monitoring because it makes it difficult to differentiate between biosimilars when monitoring adverse events. However, it has also been noted that as the FDA has stipulated that each biosimilar has a random, four-letter suffix as a unique identifier to the drug’s molecule name, this issue should not arise, as drugs can be identified using these suffixes.

Another reason why groups lobbied to change CMS’ HCPCS codes for biosimilars is that the codes did not recognize the difference between interchangeable biosimilars and noninterchangeable biosimilars. In the United States, interchangeability designation may be awarded to certain biosimilars that have shown through clinical trials that a patient can be switched from a brand to a biosimilar of the same biologic multiple times without any detrimental outcomes. The first biosimilar to achieve this status is rewarded with one year’s exclusivity as the only interchangeable available for a reference biologic. As yet, no interchangeable biosimilars are available in the United States (FDA guidance was rolled out earlier this year). Given that interchangeable designation may encourage physician prescribing of a certain biosimilar, it therefore follows that physicians should be able to make a clear choice to prescribe that biosimilar (under the old structure, grouping of biosimilars under one code was likely to make it more difficult for physicians to select a particular biosimilar to prescribe2).

Why The New HCPCS Coding Structure May Not Hold All The Answers

CMS originally introduced the idea of including all biosimilars under the same HCPCS code in order to stimulate a competitive biosimilar market, and, as discussed, it certainly would have encouraged competitive pricing (though potentially to the eventual detriment of some manufacturers). However, giving each biosimilar its own HCPCS code removes some of the pressure for biosimilars to drop their prices as low as they may have gone because they are no longer jostling for position within one reimbursement group. While pricing competition between biosimilars is still likely to be competitive as they vie for inclusion on payer formularies, the drivers for increased prescribing of biosimilars will really come when cost savings are passed on to patients via lower copays, something that physicians in the United States have reported is not generally the case.

As new, premium-priced brands emerge in the future, physicians are likely to be incentivized to prescribe these over biosimilars of other drugs, as the 6 percent fee will equate to a larger payment. So, this new ruling from CMS may not do much to encourage the use of cheaper biosimilar drugs, particularly if there’s a lack of other incentives for physicians to prescribe these drugs, such as lower costs to patients (which does currently appear to be the case, as mentioned previously). Interestingly, the Obama administration’s policy to reform the payment from ASP+6 percent to ASP+2.5 percent plus a $16.80 per day administration fee could have impacted biosimilar uptake, as the financial incentive for physicians to prescribe a more expensive drug would have been lessened (however, this policy did not come to fruition, and in the scenario where few other drivers exist for physicians to prescribe biosimilars, this policy may not have had a large impact).

A key question is what the new CMS coding means for interchangeable biosimilars. Considering the safety of switching an interchangeable biosimilar will have been proven, the biosimilar could in theory be given the same HCPCS code as the brand. This could be a method to drive both development of interchangeable biosimilar drugs and biosimilar uptake. Inclusion in the same HCPCS code as the brand would likely facilitate uptake of an interchangeable and provide a greater incentive for companies to commit to the extra clinical trial burden of developing these products. Also, including the interchangeable in the ASP calculation would likely encourage use of the interchangeable, as the financial reward to prescribers would be greater for the interchangeable biosimilar, as its acquisition cost would more than likely be lower than the ASP+6 percent. A similar policy was proposed by MedPAC in June 2017,3 except that body recommended that a consolidated billing code be established to group a branded biologic with all of its biosimilars in order to spur pricing competition. Indeed, the document noted that the ASP payment system encourages price competition between generics and their brands in a similar way. However, given the recent CMS decision regarding the adoption of HCPCS codes for biosimilars, this scenario is unlikely to be adopted.

What’s In Store For The Future

While many stakeholders are happy with the announced CMS coding changes for biosimilars, there are still many issues to be resolved to encourage uptake of these drugs in the United States, and the change in CMS policy may do little to aid this in the long term. Beyond the physician acquisition costs of these drugs, incentives such as lower costs to patients (despite reduced prices vs. reference brands, patient out-of-pocket costs can still be substantial) are top of mind for many prescribers and need to be addressed by key parties to drive their uptake.

References:

- https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/2017Downloads/R3854CP.pdf

- https://biologicsprescribers.org/press-releases/physician-groups-urge-cms-to-adopt-unique-billing-codes-for-biosimilar-reimbursement-policy/

- MedPAC Report to the Congress, Medicare and the Health Care Delivery System, June 2017

About The Author:

Amy Duval, M.Res., is a senior director in the biosimilars team at Decision Resources Group. She manages a team of analysts who conduct extensive primary market research focusing on physician and payer perspectives on biosimilars and secondary market research into the competitive and regulatory landscape for biosimilars. Ms. Duval also provides client support across Decision Resources Group biosimilars products.

analysts who conduct extensive primary market research focusing on physician and payer perspectives on biosimilars and secondary market research into the competitive and regulatory landscape for biosimilars. Ms. Duval also provides client support across Decision Resources Group biosimilars products.

Previously, Ms. Duval worked as a senior director in the oncology team at Decision Resources Group, where she built expertise in multiple oncology indications including breast and ovarian cancers, and worked on topics in both the major and emerging pharmaceutical markets. She earned her B.Sc. in natural sciences and M.Res. in molecular and cellular biology from the University of Birmingham, where she conducted research into the epigenetics of leukemia.