Drug Coupons: An Ongoing Debate Between States, Payers, And Manufacturers

By Stephanie Hoops, Decision Resources Group

Law allowing coupons expires Jan. 1, 2020 unless legislature acts

The clock is ticking for state lawmakers to preserve an existing law that allows for prescription drug coupon usage in Massachusetts with an end-of-the-year deadline fast approaching.

Drug manufacturers are anxiously awaiting this legislative action, as a ban on coupons would stick consumers with more of the cost when purchasing brand name drugs, which typically come with higher cost-sharing than generic equivalents. Massachusetts Senate Bill 2397, introduced on November 14, would allow the continued usage of coupons through Jan. 2021.

GlaxoSmithKline was among the stakeholders that submitted written testimony to the state recommending Massachusetts continue allowing drug coupon programs for patients unable to access medicines or vaccines through third-party coverage.

“GSK’s patient assistance programs provide medicines and vaccines at no cost to eligible patients,” wrote GSK VP of U.S. Public Policy Margaret Nowak Mann.

The Massachusetts Association of Health Plans also submitted testimony, arguing that while a drug coupon reduces the out-of-pocket costs, it does not reduce the price a payer would pay for the drug.

“The long term effect of drug coupons is to increase drug prices and premiums by making consumers insensitive to drug prices, thereby allowing manufactures to increase the list price of drugs without losing market share. This market distortion results in higher drug prices that negatively impacts all consumers,” wrote Sarah Chiaramida, VP of public programs and advocacy and general counsel.

Zach Stanley, VP of public affairs with the Massachusetts Biotechnology Council (MassBio) trade group, said the debate about drug coupon usage in Massachusetts ignores the patient’s lack of choice concerning prescribed drugs. Stanley points out that prescription drugs are currently prescribed based on such considerations as formularies, tiers, and prior authorization.

“In our view, that is what makes the decision about what a patient ultimately receives, not whether or not they have a coupon,” he said. “I think we’d like that to be recognized during the debate about whether the coupon program should be continued in Massachusetts.”

Whereas most states in the country have not implemented drug coupon bans, in Massachusetts and California a law must be proactively passed to enable prescription drug coupon usage. This is because the current law in these two states makes them illegal. Considering that Massachusetts is the nation’s health pioneer, having led in expanding health insurance coverage, a shift in policy with respect to coupons could be a harbinger of copycat laws in other states.

The existing Massachusetts law permits manufacturer coupons, discounts, product vouchers, and other reductions for drugs that don’t have AB-rated generic equivalents. The coupon must be given directly or electronically to an individual through a point of sale or mail-in rebate, or through similar means. Note that “similar means” is not defined, so the manufacturer’s general counsel would need to determine how broadly to construe that verbiage. Also, manufacturers must not exclude any pharmacy from being permitted to redeem the discount, coupon, rebate, product voucher, or other expense reduction offered to a consumer.

In 2012, Massachusetts relaxed the state’s anti-kickback law to permit drug coupons for those therapies that don’t have generic equivalents. Since then, the state legislature has allowed this relaxation of the anti-kickback law to continue by taking action every two years. But the last extension was through Jan. 1, 2020, and since there’s been no action, manufacturers are concerned.

The last reiteration (in 2018) ordered the state’s Health Policy Commission (HPC) to study the use of coupons and issue a report, which will presumably influence legislative action.

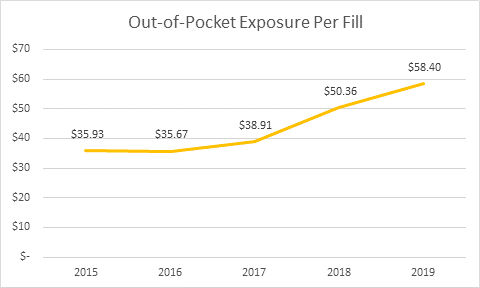

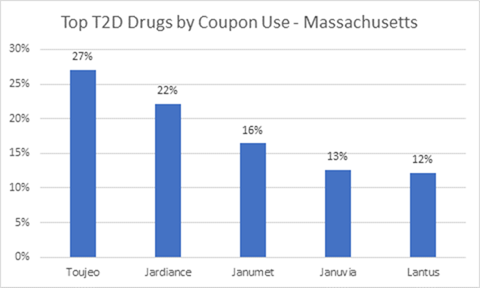

The HPC released its preliminary report findings on Oct. 2, 2019: Diabetes therapy, including insulin, is the top category of coupon use by volume. Coupon availability and use for diabetes has grown significantly, and spending per person has more than doubled for the period studied (2013 to 2018). Spending per person went from $1,891 to $3,838. The average patient out-of-pocket exposure per claim for branded diabetes therapy products rose 50 percent, from $38 to $57.

Images credit: Decision Resources Group

Although the 2018 reiteration of the law does not specify when the HPC must issue a final report, it is presumed to be in the works. Some of the information being sought includes comparisons of any changes that occur in generic drug or therapeutically equivalent brand use versus the brand name drugs, an analysis of the impact coupons may have on healthcare premiums, and how patients fare financially following the expiration of a coupon.

All of this said, drug coupons have not been as large a target for state lawmakers as copay accumulator programs have. The programs, which are a payer-driven utilization management tool, block insurers from allowing drug coupons and other copay assistance to count toward the consumer’s deductible or out-of-pocket maximum. Payers argue that as consumers ultimately become accustomed to lower-priced drugs, payers must cover the cost, which in turn drives higher premiums. Arizona, Virginia, and West Virginia this year adopted bans on copay accumulator programs. Other states have considered bans, including New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Michigan, but those bills haven’t progressed to date.

About The Author:

Stephanie Hoops is an attorney and authority on healthcare policy and regulatory issues. She joined DRG in 2015 and covers the California market. A former award-winning journalist in California and Alabama, her work has appeared in Bloomberg, Texas Lawyer and the National Law Journal. Follow her on Twitter at @StephHoopsDRG.

Stephanie Hoops is an attorney and authority on healthcare policy and regulatory issues. She joined DRG in 2015 and covers the California market. A former award-winning journalist in California and Alabama, her work has appeared in Bloomberg, Texas Lawyer and the National Law Journal. Follow her on Twitter at @StephHoopsDRG.