Strengthening Shop-Floor QA From The Ground Up

By Christian Gausepohl, Ph.D., GMP Compliance Adviser

The existence of a pharmaceutical quality system (PQS) is required by all GMP regulations. This makes it all the more surprising that there are no requirements regarding the organizational form, the role within the company, or even a management function.

Regardless of the fact that no specific requirements have been defined, quality assurance (QA) has become established as a standard functional unit in pharmaceutical companies. The role and form of this unit depends on the size and complexity of the company.

The lack of specific requirements also has a positive side: each company can optimally adapt the organization of quality assurance to its own needs!

One possible variant — the shop-floor QA — is presented below.

Quality Oversight At The Operational Level

Integrating the QA function into operational processes and daily production operations on site — also known as shop-floor QA — can offer many advantages. After all, quality is created directly on site in the operational environment and not through later inspection. Compliance with the specifications and continuous monitoring and improvement of them contribute to robust processes and quality systems. The focus here is on cooperative collaboration with the operational area and not on pure monitoring as a quasi-police function — although factually correct reviews are a matter of course.

The goal of implementing shop floor QA is to enable:

- direct on-site support of the operational areas over production shifts on all working days,

- direct and prompt involvement in problems and potential problems as well as participation in investigations,

- regular checks and observations in the operational area.

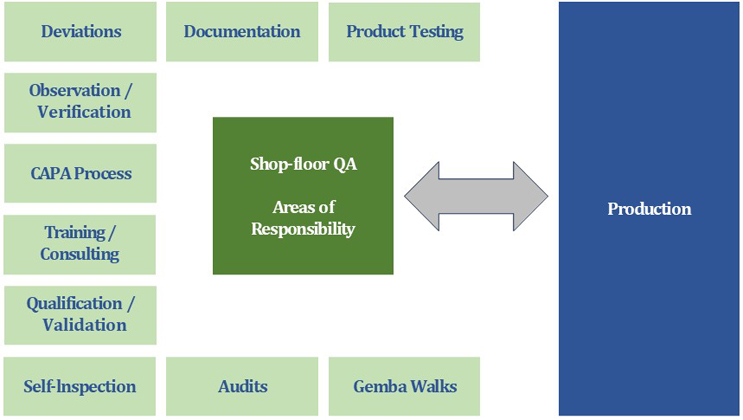

Figure 1 shows an overview of the possible areas of responsibility of a shop floor QA organization. The individual aspects are presented below under the assumption that QA is fully involved in the working shifts.

Figure 1: Possible areas of responsibility for shop floor QA

Observation And Verification

Carrying out inspections and observing activities and production process steps is a sensitive issue. Common rules and objectives should be agreed upon between operations and shop floor QA.

It can therefore make sense to carry out unannounced inspections and monitoring in order to obtain a representative picture from these observations, which — in contrast to an announced inspection — is not influenced by conscious or unconscious changes in behavior. The observed activities and process steps should not be influenced in order to avoid risks to products or processes. Addressing the personnel and intervening in the process should be avoided. However, if a risk arises due to a significant discrepancy with the standard process, direct intervention is required.

For the normal observation of activities and processes in grade A/B/C cleanrooms, these are not entered by shop floor QA in order to avoid risks to process and product safety. Viewing windows installed facing the cleanroom area are used here, and video recordings can also be used, if available. In exceptional cases, e.g., for special problems, shop floor QA representatives can also be present directly in the cleanroom. This requires prior consultation and approval and takes into account the maximum number of people permitted in the room. It goes without saying that only qualified personnel may enter the room and that the impact on the environment and the process must be kept to a minimum. The procedure must be defined and the risks assessed in advance.

It is advisable to standardize the processes related to inspections, observations, documentation, communication, and actions as much as possible. Both operational staff and shop-floor QA staff should be assessed objectively and perform objective assessments. The criteria and level of detail must therefore be defined in advance and should be clearly communicated. Standardized checklists reduce the documentation effort and facilitate objective observations. The use of this assessment should be regulated in advance. For example, it can be integrated into a shift report to ensure transparency and traceability.

Photos of anomalies may be useful for documentation purposes, as long as they help to describe the problem and subsequently serve as a starting point for problem-solving.

The results of the observations, including all anomalies, are discussed with the production team. It is advisable not only to discuss anomalies or negative observations, but also to actively and positively point out the absence of anomalies, e.g., compliance with all requirements. Prompt discussion enables solutions to be found quickly and, if necessary, training measures may be initiated.

The procedures for observing or verifying critical steps as a level of quality oversight should be evaluated and approved in advance by QA. The so-called dual control principle (doer–checker) is still used in many cases if the processes are not monitored by other measures.

Figure 2 shows an exemplary overview of the various requirements and activities of the controller.

| Risk | Activity by person 1 | Possible error | Check by person 2 | Timepoint of performing check |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low |

Manual transfer of data Manual calculations |

Error in copying Error in calculation |

Checking calculations or copying of data and confirmation | After execution |

| Medium |

Manual activities, e.g.,

|

Wrong execution (but with audit trail, etc.): Error detectable only at later timepoint |

Visual check for proper execution Later checks also possible if justified by risk assessment |

After execution (risk based) |

| High |

Critical manual activity, e.g.,

|

Wrong execution: No longer traceable | Visual check for proper execution | During execution |

Figure 2: Risk-based definition of control steps

The critical checks include, for example

- Observation of critical steps (e.g. manual aseptic process steps or interventions, aseptic process simulation [APS])

- Observation of cleaning and disinfection steps, maintenance work

- Verification of successful and complete line clearance

Self-Inspections, Audits

Shop-floor QA provides support in the planning, implementation, and follow-up of self-inspections. These inspections can be carried out effectively and efficiently thanks to detailed process knowledge and experience.

In addition, checklists for daily inspections can help to standardize the procedure, and define observation priorities, and communicate their importance through daily reviews. This helps to raise employees’ awareness of the issues. Photos can be used to address and rectify weaknesses and problems (if this has been agreed in advance by all persons concerned).

Typical points included in such checklists are:

- Corridors, rooms, facilities: Cleanliness, defects

- Clothing: How it is worn, following gowning procedures

- Observed activities: Aseptic working methods, handling of materials, transport

- Documentation: Logbooks, cleaning protocols

- Special observations

- Pictures (with the consent of the persons concerned and in compliance with previously agreed internal rules)

QA also acts as a point of contact and, if necessary, serves as a technical expert for external audits or inspections by the authorities.

Gemba Walks

In addition to regular self-inspections, it also makes sense to integrate shop-floor QA into additional Gemba walks. The term "Gemba" comes from the Japanese and refers to the actual workplace where value creation takes place.

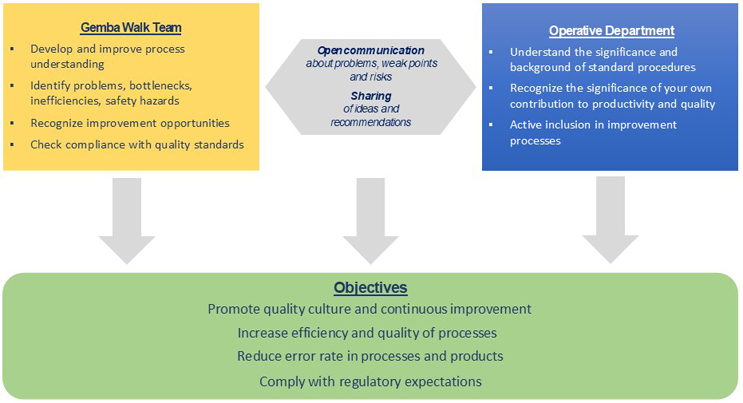

In this practical tool from lean management methods, a Gemba-walk team regularly visits operational areas such as production, laboratories, and technical spaces. Gemba walks aim to promote the quality culture and continuous improvement in the long term (see Figure 3).

Other objectives include increasing productivity by improving the efficiency and quality of processes, reducing error rates in processes and products, and improving compliance with regulatory requirements.

Figure 3: Aspects of Gemba walks

In addition to QA, the Gemba walk team includes managers from the operational area. It has proven useful to supplement the team with “internal customers” on an ad hoc basis, e.g., supply chain planners or purchasing. This can improve the internal exchange and mutual understanding of the tasks within the company.

Figure 4 shows an example of the composition of the Gemba walk team and the frequency of inspections.

| Gemba Walk Team | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Direct line manager or group leader |

every shift |

| Shop floor QA |

every shift |

| Department management |

daily (across shifts) |

| Head of production/quality control/quality assurance |

weekly |

| Plant management |

monthly |

| Internal customers (supply chain planning, purchasing, etc.) |

annually |

| Other internal resources (human resources, finance) | annually |

Figure 4: Gemba walk teams

When performing the Gemba walk, it is essential that communication is open in both directions and that the event does not take on the character of an audit. The aim is for the Gemba walk team to understand and dive deep into the processes; identify potential problems, bottlenecks, inefficiencies, and safety risks; recognize opportunities for improvement; and check compliance with processes and quality standards.

For the operations department, there is the opportunity to develop an understanding of the importance of specifications or processes via background information. The perception of one’s own contribution as an important part of productivity and quality — as well as active involvement in the improvement process, bringing ideas and discussing potential solutions both as affected parties and technical experts — are important aspects in improving quality culture and enabling continuous improvement.

Establishing and following basic rules for Gemba walks contributes to their success, for example:

- Avoid general complaints or apportioning blame.

- Do not defend the status quo or personal views without facts.

- Focus not only on problems and their solutions but also on the recognition of positive achievements and accomplishments.

How To Successfully Implement Shop-Floor QA

For the successful introduction of operational quality oversight into the company, there are a number of aspects to consider.

Such an introduction is a conscious decision for cooperation between QA and operations. It offers the opportunity to break down barriers between departments. Basically, it takes time, resources, and support from management to make this a lasting success and to realize the potential benefits. The aim is to find a good balance between control functions and cooperation on problems and improvements.

Figure 5 shows an overview of the success factors of such a shop-floor QA based on actual experience.

| Success factors for operational Quality Assurance (shop floor QA) |

|---|

|

Figure 5: Success factors for shop-floor QA

An essential basis for cooperation is that the QA employees are accepted by the operations employees. The following factors play an important role here:

- Experience and knowledge of products and processes and the quality requirements

- Communication skills

- Decision-making ability

- Ability to deal with conflict

Important QA tasks are of observational and evaluative nature, meaning that operations employees may be irritated by negative feedback. This may lead to heated discussions about the competence and experience of QA employees. Soft skills such as the ability to communicate effectively, to make decisions, and to deal with conflict are therefore important in addition to professional competence. Careful consideration must be given when assigning QA employees to oversee people who may have once been their peers. Interpersonal conflicts are a risk.

When introducing the shop-floor QA model, existing QA teams or employees can help ease the transition, especially if they're operations-oriented and have experience coordinating at a detailed level. The joint integration and use of lean management tools in day-to-day operations, such as Visual Management, 5S, Kaizen or Standard Work, makes it possible to grow together, develop, and improve continuously.

The implementation process should be monitored by managers. It must be made clear that the main purpose of monitoring is to improve processes and products and thus ultimately patient safety. This should be communicated as a common goal. Shop-floor QA should not see itself and carry itself purely as a supervisory unit.

This article is an excerpt from GMP knowledge contained in the online portal GMP Compliance Adviser, which provides in-depth information about GMP best practices and regulations with a focus on Europe but also referring to the U.S., Japan, and others (PIC/S, ICH, WHO, etc.).

About The Author:

Christian Gausepohl, Ph.D., is a global quality director and qualified person responsible for quality and compliance issues. He has worked in many different positions and has extensive audit and inspection experience with authorities, customers, and suppliers. His main concern is the practical implementation of GMP requirements. He started his professional career in galenic development in 1998 after graduating in pharmacy and receiving his Ph.D. in pharmaceutical technology. He held managerial positions in production, validation, and technology transfer; was responsible for quality assurance and quality control; and was involved in developing a robust QM system. He works for national and international organizations and associations and lectures on issues that affect the practical implementation of GMP requirements. Reach him at christian.gausepohl@outlook.com.

Christian Gausepohl, Ph.D., is a global quality director and qualified person responsible for quality and compliance issues. He has worked in many different positions and has extensive audit and inspection experience with authorities, customers, and suppliers. His main concern is the practical implementation of GMP requirements. He started his professional career in galenic development in 1998 after graduating in pharmacy and receiving his Ph.D. in pharmaceutical technology. He held managerial positions in production, validation, and technology transfer; was responsible for quality assurance and quality control; and was involved in developing a robust QM system. He works for national and international organizations and associations and lectures on issues that affect the practical implementation of GMP requirements. Reach him at christian.gausepohl@outlook.com.