Why So Slow? Demystifying The Barriers To U.S. Biosimilar Adoption

By Christina Danosi, Alexandra Haber, Nicholas Simmons-Stern, John Greenaway, and Jillian Godfrey Scaife, Trinity Partners

Despite past years’ optimism about the potential cost savings of biosimilars, recent market trends show U.S. biosimilars lagging behind their reference drugs in market share.1 Most notable is Pfizer’s Inflectra — the first biosimilar of J&J’s Remicade (infliximab) — which has garnered less than 4 percent share of molecule sales as of September 2017.2 In September, Pfizer filed a lawsuit against J&J, openly blaming the manufacturer’s “exclusionary contracts,”3 wherein large rebates combined with payer preference of the originator drug prevent a cost-effective coexistence with the biosimilar.4 With these contracts, payers attempting to split volume between Remicade and Inflectra lose their Remicade rebates and thus spend more overall for infliximab; meanwhile, a complete switch to lower-priced Inflectra is not yet possible due to lack of brand-biosimilar interchangeability.

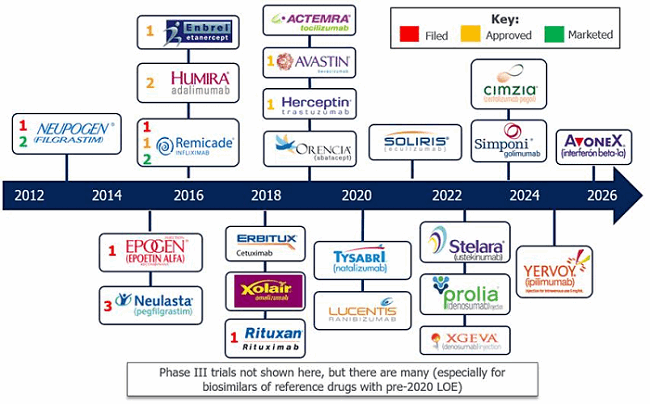

This article will provide a glimpse into the complex and often misunderstood dynamics of U.S. biosimilar reimbursement that contribute to the state of the market today — a topic that is particularly salient in light of recent policy changes by CMS.5 Due to those changes, upcoming biosimilars (Figure 1) may have a significantly different experience than those already on the market, but it is important to understand the environment in which the earliest launches have underperformed so far.

Figure 1: Loss of exclusivity (LOE) and biosimilar entry timeline — LOE is approaching for many biologics, priming the market for more biosimilar entry.

Biosimilar Economics and Contracting Dynamics

Contracting dynamics are a major contributor to the slow adoption of biosimilars. Biosimilar manufacturers initially thought payers would champion biosimilars because of the potential cost savings, driving prescribing and uptake. Expecting favorable formulary placement, Sandoz was not worried that its Neupogen biosimilar, Zarxio, did not have interchangeability status: The company assumed payers would “push lower-priced products, despite efforts by innovator firms to label biosimilars as lower quality because they’re not interchangeable”.6 However, brand-name biologics manufacturers attempting to protect their market share have implemented strong contracting strategies with both providers and payers to make a rapid switch to biosimilars unlikely.

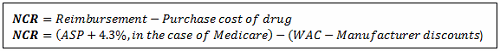

At the root of the problem is a complicated pricing and discounting system that extends beyond a biosimilar’s list price — or wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) — and leverages a web of reimbursement dynamics pertaining to physician-administered buy-and-bill therapies. (“Buy-and-bill” drugs are purchased by physicians, administered to the patient, and then billed to Medicare — or commercial payers — and the patient afterward for both the drug and the administration. This includes Medicare Part B drugs.) Although biosimilars are publicly priced at a discount (WAC typically ~15 percent of the reference product’s), most distributors, group purchasing organizations (GPOs), and providers never pay the WAC price due to discounts and rebates from the manufacturer. Payers do not reimburse at WAC either (except in the first ~2–3 quarters immediately after launch). Rather, reimbursement is based on the “payment limit” published quarterly by CMS. In every quarter, CMS collects manufacturer-reported commercial sales volume and price concessions (i.e., discounts or rebates) over the past four quarters for each drug with a unique J-code, in order to calculate the average selling price (ASP) of the drug. They then add a cushion of 6 percent on top of that ASP to determine the payment limit or “allowable” that goes into effect two quarters later (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Average selling price (ASP) calculation

(Note: Price concessions included in the calculation of ASP do not include sales at mandated federal pricing [PHS, VA/DoD, Medicaid] or any bone fide service fees to wholesalers. Many commercial payers reimburse at a rate higher than the 6%, while Medicare reimburses at a lower rate of 4.3% due to the federal budget sequestration of 2013.)

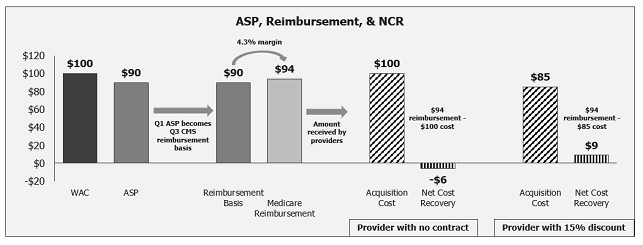

Payment limits posted by CMS dictate how much a provider will be reimbursed for using a product (Figure 3), which factors into the provider’s net cost recovery (NCR) equation — the difference between the price paid for the administered drug and the reimbursement received from the payer (Figure 4). If reimbursement is greater than cost, the provider’s NCR on the product is positive; if reimbursement is less than cost, NCR is negative (also referred to as “being underwater”). The cost side of the equation is dictated by contracted concessions from manufacturers to providers, which may vary across providers and can depend on performance metrics like drug volume or share; therefore, some clinics or hospitals may pay a lower price than others and thus maintain a higher NCR.

Figure 2: Reimbursement calculation (Medicare example)

Figure 4: Net cost recovery (NCR)

Meanwhile, manufacturers also contract with payers, providing rebates that lower their costs. The goal of these payer contracts is to increase access to the contracted product, typically via preferred formulary tier placement or reduced barriers such as prior authorizations or step edits (a common management tool requiring the patient to try a preferred therapy before the requested one). In this way, both payers and providers benefit from manufacturer contracting via per-unit cost savings, and, in return, manufacturers may obtain better access from payers and higher market share at contracted provider institutions. This web of contracting leads to a gap between WAC and ASP that is often overlooked in discussions surrounding the cost of pharmaceuticals, as true cost to the system is dictated by ASP, on which reimbursement is based. A first-to-market biosimilar that launches to headlines of “steep discount compared to [the originator product]!” often receives those headlines because of a WAC discount. This kind of headline, which was exemplified by the recent Inflectra launch, leaves out the much more important question of ASP comparison. Because Remicade’s Q1 2017 ASP ($808) was far below its WAC in that quarter ($1,167), while Inflectra was reimbursed at its WAC ($926) at launch (like all newly launched buy-and-bill products), Inflectra was actually more costly to the system in its early quarters despite its lower list price. This important (albeit short-lived) feature of pricing at launch can handicap early access and sales for the first-to-market competitor.

Prior to November 2017, this disadvantage primarily affected the first-to-market product while sparing later entrants due to a seemingly small nuance: because all biosimilars for the same reference product shared a single J-code, they also shared a single ASP. CMS combined all the biosimilar products’ sales and price concessions to create one shared payment limit for reimbursement; therefore, contracting decisions made by any one biosimilar manufacturer impacted not only their own product’s economics, but also their competitors’. This meant that in the world of biosimilars, the usual “first-mover advantage” could easily go to the second-to-market biosimilar: the first-to-market manufacturer would have to contract with payers to bring the net cost (to payers) below that of the reference product, those concessions would decrease ASP (and thus reimbursement) two quarters later, and the second biosimilar could immediately reap the benefit of that lower cost to payers. (Beyond the shared J-code, biosimilars were also linked directly to the reference product because the margin paid to providers [4.3%, 6%, or higher] was a percent of the ASP of the reference product rather than of the biosimilar.)

The infliximab market is a perfect example of this phenomenon, where the ASP of incumbent Remicade was already far below WAC due to years of contracting when Pfizer launched Inflectra at a price above that ASP. As a result, Pfizer would only have been able to match or beat Remicade’s cost via aggressive payer contracting. It is possible that a failure to contract with payers to a sufficient degree at launch led to Pfizer’s early struggle to gain payer coverage and thus market share: In their Q2 2017 earnings call, Pfizer reported: “To date, reimbursement coverage [of Inflectra] has been mixed. … We have experienced access challenges among national commercial payers where our lower-priced product has not received access at parity to [Remicade] and remains in a disadvantaged position.”7

Second-to-market biosimilar Renflexis joined the melee in Q3, automatically receiving reimbursement at Inflectra’s Q3 payment limit of $787 (which had dropped from the original $926 due to the contracting Pfizer did pursue). This gave Renflexis the bizarre (and temporary) trait of an ASP over $30 higher than its list price ($753), which is appealing in terms of provider NCR. This ASP was also lower than Remicade’s ($871), thanks entirely to Pfizer concessions and possibly sparing Merck’s Renflexis the pain of Inflectra’s access issues.

Notably, the CY 2018 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) Final Rule in November ended the shared J-code: “Effective January 1, 2018, newly approved biosimilar biological products with a common reference product will no longer be grouped into the same billing code” (section III.D).5 The separation means that starting January 1, 2018, competing biosimilars will be treated like any other branded competitors in a market. A brand’s contracting activity will only affect its own ASP and reimbursement. Other barriers to biosimilar uptake — including contracting by the originator company, lack of interchangeability, and physician reluctance to switch — still remain, but this change removes a significant layer of additional complexity.

On the nascent and uncertain frontier of biosimilar commercialization, the industry and regulatory bodies are learning as they go. The recent rule change reflects this. As CMS notes, “This policy change will result in the licensing of more biosimilar products, thus creating a stable and robust market, driving competition and decreasing uncertainty about access and payment.” The policy change, however, does not lessen the importance of considering reimbursement dynamics in ongoing and future biosimilar commercial planning. While the new CMS rule will eliminate the “second-mover advantage” discussed above, biosimilar manufacturers should still consider originator ASP (not WAC) as the key reference point when determining their own WAC price, and should develop contracting strategies if they have hopes of initiating stronger payer support and faster conversions from originator products. Going forward, the expectation is that biosimilar ASPs will naturally fall over time and help them gain favor with payers, while physician and patient skepticism towards biosimilars will simultaneously decrease. However, interchangeability and competitive contracting both remain hurdles, and upcoming Trinity research with payers will explore these topics in more detail, providing an insider look at the future of biosimilars.

References:

- Mavroudis-Chocholis, Orestis. “The U.S. Biosimilar Market: Where Is It Today, and Where Is It Going?” July 2017. www.biosimilardevelopment.com.

- Pfizer v. Johnson & Johnson, 2017. www.documentcloud.org/documents/4056419-Pfizer-v-Johnson-Johnson.html.

- Rockoff, Jonathan D. “Pfizer Alleges J&J Thwarted Competition to Remicade, in Legal Test of Biotech-Drug Copies.” The Wall Street Journal, September 2017.

- Hakim, Aaron. “Obstacles to the Adoption of Biosimilars for Chronic Diseases.” JAMA, May 2017.

- CY 2018 PFS Final Rule. Federal Register, Vol. 82, No. 219, p. 53186, November 2017. https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2017-11-15/pdf/2017-23953.pdf

- Wechsler, Jill. “Does Interchangeability Really Matter for Biosimilars?” Pharmaceutical Executive, November 2015. www.pharmexec.com/does-interchangeability-really-matter-biosimilars.

- Q2 2017 Pfizer Inc Earnings Call, August 1, 2017. https://s21.q4cdn.com/317678438/files/PFE-USQ_Transcript_2017-08-01.pdf