Should Your Biosimilar Really Be A Biobetter?

By Anna Rose Welch, Editorial & Community Director, Advancing RNA

When choosing biosimilar conferences to attend, I’m often drawn to panels that discuss making the choice between biobetters and biosimilars. Part of my interest has to do with the fact that “biobetter” is a tricky, non-regulatory term which many argue should be done away with. Then there’s the fact many of the reference companies, in the face of biosimilar competition, have chosen the biobetter route as a strategy to stay afloat. But I find the debate of biosimilar vs. biobetter particularly valuable, given the importance for biosimilar companies to differentiate their products.

So, you can imagine my interest was piqued when I heard a few months ago that Eagle Pharmaceuticals had agreed to acquire Arsia Therapeutics. Eagle, which has a sturdy reputation in the small molecule space, will be using this acquisition as a way to enter the biologics market — specifically, the biosimilars space. Thanks to Arsia technology, Eagle will be able to partner with biosimilar companies to help turn biosimilar candidates into biobetters.

As Eagle CEO Scott Tarriff describes, the company’s established business model of reformulating and improving existing small molecules is also well-suited to the biologics space — especially considering his expectations of how the biosimilar space will play out.

The pharma industry is currently encountering stringent pricing pressures, and analysts and economists have argued that higher-priced innovator biobetters won’t necessarily trump biosimilars in payers’ eyes. But Tarriff expects, with the right price, biobetters can hold their own on the market.

“In this large biologics market, launching a biobetter at the same price as the biosimilar will be extremely valuable,” Tarriff argues. “If there are three companies coming out with the same product, and one of them has an improved formulation and winds up getting two-thirds of the market, that would likely make up for the smaller price.”

Where Is The Biosimilar Space Headed?

As the biosimilar industry has grown in the U.S., we’ve been reminded biosimilars are going to be treated differently than small molecule generics. In fact, we just saw two FDA guidances released (biosimilar naming and interchangeability), both of which establish these differences. The biosimilar industry’s upset over the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS’) reimbursement policy, which treats biosimilars as small molecule generics, also suggests biosimilars fall somewhere in the middle of the innovator to generics spectrum.

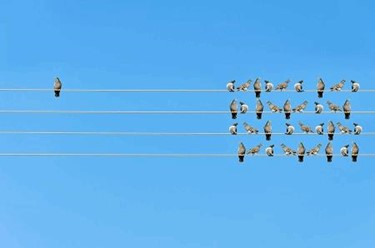

Because of biosimilars’ hybrid nature, one of the questions I like to ask people is where they see the biosimilar industry ending up in the next five to 10 years. Will we see uptake and competition similar to that of the generics market? Tarriff strongly believes the biosimilar market is poised to be like the generics space in terms of competition. As he describes, there are a growing number of players focused on supplying the biosimilar market with high-quality biosimilars.

“By definition, all of these products are going to be very similar, if not exact, to each other,” says Tarriff. “In my view, that’s the definition of a generics market.”

However, pricing is one of the biggest areas of concern in the biosimilar space. Because of the high investment to develop biosimilars, pricing cannot be a race-to-the-bottom like we saw in the ’80s with generics. (This is why, when Sanford Bernstein Analyst Ronny Gal predicted future price cuts of 75 percent for biosimilars at the 2016 GPhA Biosimilars Council conference, there was a slight shiver that swept through the conference room.)

Right now, we see a sizeable group of companies dedicated to developing biosimilars and hoping there won’t be large decreases in price. And so far, in the U.S. and Europe (not including daring Scandinavia), steep discounts haven’t become as big of a concern given the limited number of competitors. But as Tarriff argues, it won’t always be this way.

“I feel a lot of companies are spending tremendous amounts of money to enter a new, very large generic drug business,” he says. “Depending on the product and a company’s time frame for entering the market, it might be better to invest in improving formulations to get a leg-up on the other biosimilars coming to market.”

For instance, should a company arrive to the marketplace late with a biosimilar that already has several competitors, coming up with a biobetter version might also help it compete against the reference product, in addition to the other biosimilars.

One option is to take an IV-administered biologic and create a subcutaneous (SC) version. In fact, in recent months, we saw Roche come out with a subcutaneous version of Rituxan. (But in the case of SC biobetter rituximab competitors, at least, we might have to wait awhile. Celltrion recently released a statement saying it’s too early to reveal an SC development plan for its rituximab biosimilar Truxima.)

So, while some biosimilar candidates will come to market in the original formulation of the reference biologic, others could jump ahead in order to compete against the reference product’s new formulation. This is the main goal of Eagle’s venture into the biologics space.

“We want to give a biosimilar company the opportunity of catching up to, say, Roche, by helping them develop a subcutaneous version rather than an IV,” Tarriff explains.

The Challenges Of “Leap-Frogging” Biosimilars

There are a couple of different partnership strategies Eagle and a biosimilar company could establish. One would be to help a biosimilar company develop, for instance, an SC version of an IV drug which has already been released in an SC formulation by the innovator. The other option would be to help a biosimilar company usher its candidate to market in a different formulation than that which was launched by any other biosimilar companies or even the innovator.

But the former option raises a few questions on the regulatory level. Take Rituxan as an example. Halozyme and Roche’s efforts led to the approval and release of an SC version of Rituxan. As such, the FDA has already reviewed and approved the process of taking that molecule from an IV to an SC formulation.

“We’re still unsure yet what this will mean from a regulatory standpoint for any other candidates that evolve from IV to SC when it’s already been done before,” Tarriff explains. “Will we be able to negotiate with the FDA to create some sort of bridging study in order to isolate any concerns they may have about changing the formulation?”

When I hear the term “biobetter,” I tend to think immediately of IV to SC. But we shouldn’t expect the bio space to be limited to these formulations. In fact, Tarriff expects some of the work Eagle has done in the past for small molecules could become feasible in the biologics space, as well.

For instance, when Eagle launched, its platform turned lyophilized cytotoxic drugs into ready-to-use liquids. The company then entered the chemotherapy space, in which its work with Ryanodex led to the drug being administered more quickly. As Tarriff describes, the company’s technology can reduce the injection volume of a treatment, which, in turn, shortens the time of administration. This strategy could be particularly beneficial for ocular products, like Lucentis.

“I’m extremely hopeful the biologics space will go through the same evolution, once we dig into it,” says Tarriff. “This is a very clever and creative industry. I’m sure, in time, we will find greater improvements to biologics formulations than just going from IV to SC.”